Archive for January 4th, 2009

Obamania – Obama’s Army

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Obama on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Occupy, Resist, Produce

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Credit Crunch on January 4, 2009| 1 Comment »

Chicago occupation ends in victory for workers

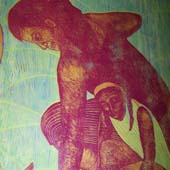

The Face of Resistance

Victory at Republic!

By LEE SUSTAR

With a unanimous vote, workers at the Republic Windows & Doors plant in Chicago ended their six-day factory occupation late on December 10 after Bank of America and other lenders agreed to fund about $2 million in severance and vacation pay as well as health insurance.

“Everybody feels great,” said a tired but beaming Armando Robles, president of United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers (UE) Local 1110.

Melvin Maclin, the local’s vice president, agreed. “I feel wonderful,” he said. “I feel validated as a human being. Everybody is so overjoyed. This is significant because it shows workers everywhere that we do have a voice in this economy. Because we’re the backbone of this country. It’s not the CEOs. It’s the working people.”

Pointing, he continued, “See that sign up there? Without us, it would just say ‘Republic,’ because we make the windows and doors. This shows that you can fight–and that you have to fight.”

The settlement was a resounding victory for union members who were told a little more than a week earlier that the factory would be closed in less than three day’s time–and that, contrary to federal law, they would get no severance pay.

So to pressure the company to make good on what it owed them, the workers voted to stay put after the plant ceased production on December 5.

By deciding to occupy their factory–a tactic used by labor in the 1930s, but virtually unknown in this country since–the Republic workers sparked a solidarity movement that forced one of the biggest banks in the U.S. to pay two months of wages and health care, even though the bank had no legal obligation to do so.

* * *

WHAT BEGAN as a resolute act of some 250 workers quickly became a national symbol of working-class resistance in a crisis-bound economy. Hundreds upon hundreds of union members and officials–not only from Chicago, but around the Midwest–came to the Republic factory to express their solidarity and bring donations of food and badly needed funds.

But support for the Republic struggle went beyond the ranks of organized labor. The fightback crystallized mass anger about the $700 billion bailout of Wall Street. Even though Bank of America–Republic’s main creditor–is in line receive $25 billion in taxpayer money, the bank refused to finance the 60 days’ pay due to workers under the WARN Act if a plant closes without the two-month notice required under the law.

Democratic politicians, from President-elect Barack Obama down to Chicago aldermen, felt the pressure to declare their support for the struggle.

Press coverage was affected as well. For once, the media not only highlighted the issues in a labor struggle, but also used its resources to investigate the employer. The Chicago Tribune reported that Republic’s main owner, Rich Gillman, was involved in the purchase of a nonunion window factory in Iowa to move to. Journalists also uncovered evidence that Bank of America refused repeated requests to extend more credit to Republic, despite its infusion of bailout money.

Thus, when UE decided to make Bank of America the target of a December 10 rally, there was a ready response–about 1,000 people turned out on short notice.

“Since we’re down here in the financial district, let’s do a little mathematics,” said Rev. Gregory Livingston of Rainbow/PUSH. “Bank of America got $25 billion. Citibank got $25 billion. Republic workers got how much? Zero.

“That’s why we’re here in the financial district. It’s where the money is. The people work, and guess whose money is in these banks? Guess whose money is in the market? Guess whose money is in their pockets? It’s our money.”

But what was noteworthy about the picket wasn’t the anger against the banks, but a palpable sense of workers’ power. Members of a dozen different unions were on hand, as were student groups, socialists and community groups, all inspired by the Republic workers’ bold stand.

Larry Spivack, regional director of AFSCME Council 31, summed up the mood in his speech. “Look around you,” he told the crowd, naming the main financial institutions nearby. “Who created all their wealth?” he asked–and was answered by the chant, “We did!” “Who has the power?” “We do!”

Spivack continued: “This is a beginning, like when the Haymarket struggle took place in 1886,” a reference to the Chicago martyrs in the struggle for the eight-hour workday. He concluded with a shout, “Power to the workers!”

A few hours later, back at the Republic plant, after workers heard the terms of the agreement and voted, Bob Kingsley, the national director of organization for UE, made a similar point in assessing the victory:

The significance of this struggle for the labor movement is that at a time when millions of American workers are facing greater and greater economic turmoil, and with it more and more instances of unfairness, there needed to be a clear symbol of resistance.

What the workers at Republic are is the face of that resistance. They personify the challenge that the working class faces in today’s economy, but they also symbolize the hope that if we, as workers, stick together, if we fight together, and if we’re willing to push the limits, we can achieve incredible things. And their victory comes at a time when the labor movement needs it.

The occupation of factories is a method of the workers’ movement usually used to prevent lock outs, which sometimes lead to “recovered factories” in which the workers self-manage the factories.

Some other examples of sit-down strikes or occupations can be seen in the Turin factory occupation of 1920, in the Polish coal-mines in 1931 and in Poland in the early 1980s, again in Italy in the 1970’s with the 35 day occupation of Fiat, also the 1971 Harco work-in and with the Lip factory in 1973, and more recently with the wave of occupations in Argentina documented in the documentary ‘The Take’ (http://www.thetake.org), and also in Germany with the Strike Bike project.

Closer to home, there has also been the UCS work-in in Scotland in 1971-1972 and again at Caterpillar in Uddingston in 1987 and Lee Jeans in Greenock, and Plessey in Bathgate in 1981.

Direct Action in Iceland

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Credit Crunch on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Since early this winter, Iceland has been facing economic crisis. The three major business banks have been nationalized, putting their dept on the people’s shoulders. People have been losing their livelong savings, loans have increased and are getting sky high (and for sure they already were high enough). 200 people lost their job, every single day of November and more and more people are facing the threat of losing their houses.

People are getting angry, some of them wanting back the “good old” prosperity, while others and hopefully the majority, are realizing the real cost of capitalism. More and more people are standing up against corruption and demanding new form of society – society of justice. But every day the current government proves that it’s main aim is to save their own and their friend’s ass. A loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been granted, most likely leading to the common aftermaths of an IMF loan: the privatization of social systems as the health care and the education system, and more destruction of the Icelandic wilderness.

Weekly demonstrations

For more than 2 months people have gathered weekly in a park in front of the parliament. The first protests demanded that the government would “break it’s silence” about the current situation. People were tired of not even being told about what was happening and what the government was doing about it.

But soon people realized that it was not enough to ask the government to speak, so the protests took up another and more radical demand: the resign of the government and new elections as soon as possible. The government has completely ignored this demand and people are getting more and more angry.

Anarchists and other radical leftists have come to most of the protests, but not to protest against the economic situation, not to ask the government for solutions, not to ask for new elections, not to ask any member of the government or parliament or any other official institution to do anything to “solve” the crisis we are facing. But to spread anarchistic and anti-capitalistic information among people, analyse the problems of authority and capitalism and to encourage Icelandic people to take direct action against the forces of corruption.

Burning of bank flags and “hanging” of a capitalist

During a protest in front of the prime minister’s office in late October, the flags of two Icelandic banks were burned. A group of anarchists, probably the biggest in Icelandic history at that time, shouted anarchistic slogans, pointing out capitalism as the real problem. Until then, capitalism seemed to be a ban-word among the protesters. The flag burning caught the interest of foreign media, e.g. CNN which showed the burning in their news show later the same evening. An event like this had not happened in Iceland for a long time.

A week later, a big demonstration parade went through the center of Reykjavík, demanding the resign of the government. Anarchists, which grew bigger and stronger every week, joined the march with banners, black flags, leaflets about direct actions, and anarchistic slogans. While other protesters chanted “Away with the government”, anarchists shouted “Never again government!”

When the parade came down the the park were weekly speeches took place, a group of people climbed a big fence and hung a doll of a capitalist. Again foreign media captured the performance on tape and screened it around the world.

Couple of meters away from the park were the protests take place, a Food Not Bombs groups has been giving away food every Saturday for the last 8 or 9 months. Food Not Bombs has for sure had it’s effect of the walking-by Icelanders, who are getting more curious and interested in alternative solutions to the problems of capitalism.

The government is a cheap and dirty pig

During a protest, Saturday November 8th, an anarchist climbed on top of the parliament were he hung the flag of Bónus, Iceland’s cheapest supermarket. The message was clear since the flag is yellow with a pink pig on it: “The government is a cheap and dirty pig!” Unlike to the usual Icelandic protesters, people celebrated this act and sang along “The government is a cheap and dirty pig!”

Soon hundred protesters surrouneded the parliment to help the anarchist to get away from the police, which had already arrested a mate of him. After a bit of a struggle with the police, people managed to help the flag-man (like he later became known as) to get down of the roof and de-arrested him more than once. One could feel some change in the air.

Illegal arrest

Less than a week later, on a Friday night, the police arrested the flag-man. He was in the middle of a research trip to the parliament, organized by his university, when some parliament staff recognized him and called the pigs.

The man had been arrested two years before, for an action with the environmental direct action campaign Saving Iceland, protesting against the building of a big dam, Kárahnjúkavirkjun, in the eastern higlands. For this action he had got sentenced and fined, but refused to pay the fine and instead insisted on sitting in jail for 18 days. But after only four days of his jail-sentence he was “thrown out” because of lack of space in the prison.

Now, the police stated that the man would have to sit the other 14 days of the sentence. The fact is though that the it is not allowed to split the sentence like this, and the man was supposed to get an announcement about finishing his sentence with at leas 3 weeks notice. This had not been done in his case.

People claimed this was especially done by the police, fundementaly to “take out” an activist who was likely to take more actions during the upcoming weekly demonstration. So the next day, during the protest which 10.000 people had joined, another protest was announced, this time in front of the police station, a little bit later that day.

Riots by the police station

500 people came to the police station and demanded that the man would be set free. After a while, no sign of the police was seen and nothing looked like the man would be set free. The protest got heated and soon people had started to break windows of the station and in the end the door of the station was broken. A group of people went in were the police welcomed them with a splash of pepper spray, without even announcing it.

The protest got even hotter, red paint and eggs were thrown at the station and on the riot squad which now had formed a chain in front of the station. A lot of people were peppersprayed, including the flag-man’s mother and young kids down to 16 years old. In the end, the flag-man was payed out of the prison by an unknown person. The flag-man came out were he was celebrated like a hero. He thanked people for the support but encouraged people to use their energy for something else: a revolution!

Invasion of the Central Bank

A week after the riots by the police station, the weekely protest was a little more chilled. Instead people hoped for something big taking place the upcoming Monday, December 1st, the day of Iceland’s sovereignty.

1st of December used to be a free day in Iceland but couple of years ago the proletariat movement disclaimed it´s right. This 1st of May people were encouraged not to pay their bills, not show up in work and come to a big outdoor meeting on a big hill close to the government offices and the Central Bank. Few speeches took place, most of the including some nationalistic piffle which the radicals answered with a slogan: “No nationalism – International solidarity!”

After the meeting was formally over the word on the street was that more radical action was going to take place. Suddenly a big group of people marched to the Central Bank and entered the first entrance.

The entrance was completely full of people shouting and demanding that Davíð Oddsson, the chairman of the Central Bank board and a former prime minister, would resign. Few policemen had closed the second entrance but people shouted at them, asked in “what team” they were in, telling them to join the public, leave the entrance and let the people in. Suddenly the police left the entrance, the people cheered and opened the door to the second entrance.

Pepper spray again?

The second entrance became completely full as well as the first one, but behind big glass doors the riot squad had formed a chain of c.a. 30 pigs, armed with shields, clubs and pepper spray. Again, instead of speaking to the people, the pigs started shaking their spray cans, forcing to use it against the people it they would not leave.

People started banging on the door, shouting slogans against the Central Bank and the police. After a while, when a police officer had several times threatened to use the pepper spray, people decided to sit down peacefully and not stand up until Davíð Oddsson would resign. The action stood over several hours and had it’s peaks when people stood up, lifted up their hands to show they were unarmed and challenged the police to leave, open the doors and let the people bring Oddsson out.

When it became clear that Oddsson had already left the building the protesters gave the police an offer: the riot squad would leave and than the protesters would leave the building. About 30 seconds later, the pigs walked back and the people cheered some kind of a victory of the people.

Into the parliament

A week later, last Monday December 8th, thirty people went in to the Icelandic parliament, heading to the inside balcony were the public is legally allowed to sit, watch and listen to what takes place there. The group announced that the parliament no longer served it’s purpose and the government should therefor resign right now, the other MP’s should use their time for something more constructive.

Only two persons got to the balcony and shouted at the MP’s and ministers to leave the building. Quickly they were brutally removed by a police officer, while the rest of the group was stuck in a staircase inside the building. The parliamentary session was delayed and all the MP’s left the room.

Meanwhile the protesters were brutally handled by security guards and police, which ended up arresting 7 people, most of them for housebreaking. But like said before, the public is allowed to enter the parliament balcony.

A government meeting delayed with human chain

The next morning, 30 people had gathered in front of the prime minister’s office were a government meeting was supposed to take place. The people had formed a human chain blockading the two entrances of the house. When ministers started to show up, the police had already arrived and started to try to remove the chain. The people resisted heavily and read out a statement sent out by the group.

The statement said that the aim of the action was to “prevent the ministers from entering the house and therefor stop further misuse of power. Money has controlled people on the cost of their rights and the authorities and their cliques have manipulated finance for their own benefits. That manipulation has not entailed in a just society, just world. Time of action has dawn, because a just society is not only possible, but it is our duty to fight for it.”

With the help of the police, all the ministers got in, but heard the statement and were under big pressure from the media. They were not prepared for questions and came out badly when asked. The government meeting was delayed because of the actions.

Two were arrested, one for entering a police line and the other one for sitting in front of the police car which was about to drive the other arrested one to the police station. More people sat on the street and it took the police quite a long time to get out of the street. Only when a police officer gave the driver an order to “just drive hard”, the driver did so and nearly drove over two persons.

One of the biggest newspapers in Iceland, DV, reported the brutal behavoiur of the police. The paper’s journalist and photographer were both attacked by the police, as well as noticing when a police punced a protester in the face, while he lay on the street. Most other media did not dare to report the brutal behaviour.

A left wing website, Smugan, told about a police officer who was asked by the protesters if he would have protected Hitler. His answer was simple: “Yes, if it would have been my duty.”

French unemployed carry out a “self reduction” in Parisian supermarket

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Misc. on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

On 31 December, 2008 over 50 unemployed and precarious workers blocked the checkout of a Monoprix supermarket in the suburbs of Paris with 13 trolleys full of food. After distributing a leaflet, demanding a “self-reduction appropriate to this time of crisis, which will allow for the precarious to celebrate New Year’s with dignity”, negotiations with the supermarket management resulted in them leaving without paying. A portion of the food was distributed to the undocumented immigrants who have occupied the Parisian labor hall.

Free Gaza / No Walls Between Workers

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Anti-militarism, Art/Design on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Protests took place in London, Bristol, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Portsmouth against the ongoing attacks against the people of Gaza. Should you wish to take action, both Bristol and Oxford have Palestine Solidarity Campaigns – see Indymedia for further information.

An anarchist reports on Gaza

It happened at 9am this morning. We were speaking to Sabrine Naim at the time, standing and talking in the Naim family home which had been wrecked this morning. Chunks of debris – one a meter long and a foot wide – glass, and sharp slices of their own broken roof, had smashed onto beds, chairs, their kitchen and living room. Only two of their family of 12 had been home at the time. They were expecting an attack.

And it came at 4am – a missile strike by an F16 on the local police station and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine offices.

Smouldering rubble and rocks and dust were strewn across the heart of Beit Hanoon – the market, taxi rank and main streat littered with debris.Sabrine had been hit in the face with small chunks of her neighbour’s home. One side of her right cheek was covered with a thick white dressing. She looked watery eyed and exhausted. Debris had also struck her in her heavily pregnant stomach. With only a month to go until giving birth, she spent two hours in the local hospital before being discharged.

The 4am blast shook us all out of our beds. A gigantic abrupt bang – the sound of concrete walls, floors and steel rods exploding on impact in an instant. The strikes had been happening all night – most of them in Jabaliya again. Distant thuds that you strain to map in your mind.

We had spent the night in Beit Hanoon, a town home to some 40,000 people in the North of the Gaza Strip. Beit Hanoon borders Erez Crossing and Houg (now called Sderot) in Israeli territory. The town possesses some of the most fertile land in Gaza. Much of it – orange groves and olive trees – has been bulldozed by the Israeli military to clear cover for fighter fire against Israeli settlements and towns. Even so, because of its’ proximity to Israeli towns, rockets have been known to be launched from here.

The family home we stayed in had been occupied by Israeli soldiers in the last invasion in 2006. The family of six was moved into the downstairs flat, whilst soldiers blasted holes in the walls of rooms on the top floor to make sniper posts. If the noise of an invasion – tanks, apaches, F16s, heavy boots, agitated soldiers and the never-ending sneer of the surveillance drones – didn’t keep the family awake. Then the sound of single shots and the wondering what or who had been hit, worrying that a neighbour or family member had been struck, would add to the internal invasion.

The house, located in a courtyard with olive trees and a roof with clear views of the surrounding streets made an excellent vantage point for snipers. Another home, of local doctor Mohammad Naim, a specialist in treating prematurely babies at Shifa Hospital had been occupied 12 times in the past 8 years by Israeli soldiers. He hadn’t even bothered to paint over the naked grey concrete smears in the walls in his upstairs room. They had been sniper holes. And he knew they would be back again.

His outside wall too, bore the spray painted orientation indicators typical of occupying soldiers moving through narrow alleys at night.

‘Do you think you’ll move if they invade?’ I asked him. ‘Where will I go?’ He said, ‘I haven’t got anywhere else to go?’. He showed me the lock of his front door, ‘This as been smashed open at least 20 times’ he remarked. Dr Mohammad had been blindfolded and taken to the agricultural school in Northern Beit Hanoon during the last invasion, along with all local men aged between 16-40.

He had been interrogated and detained from Thursday afternoon under Friday evening. ‘Every invasion they occupy my house. They cut the electricity and use their own flashlights. Last time my family were all downstairs for five days. My children are the worst affected, they remember everything, the tanks, the invasion, and being jailed; none of us are allowed to go out even when there is a break in curfew’. Asked how the soldiers behaved towards the family, he said, ‘Well it depends on the shift, sometimes they’re decent, sometimes they can be aggressive. But with the situation as it is now, any movement could attract fire’.

‘50 people were killed here’. This is my friend Sabr talking. He’s pointing to the street outside his sister’s home – another one always occupied by soldiers, like that of Dr Mohammad. In the last invasion, resistance had confronted advancing tanks. The result was a bloodbath. His family home had been leveled to the ground.

Walking through the streets here, nearly every house has a martyr – martyrdom status is attributed to anyone, young or old, fighter or civilian – who has been killed by occupation forces. It is a mark of respect, and a coping mechanism for the sheer volume of death and an inconsolable, mounting level of loss that affects every family. It is also a way to honour and pay tribute to lives violently taken, and let life live after death under occupation. Everyone knows a neighbour, a friend, a cousin, somebody who was killed by Israeli occupation forces. Communities here feel each death personally, because so many so know one another personally. The extended family lines and kinship networks that have grown up from the collective experience of dispossession and expulsion are a web of support and a common thread made solid in the form of houses built from tents, all close together and all bearingwitnesses together. Because the size of families and the proximity in which people live together, there is a natural participatory experience in almost every aspect of daily life. And every killing there is a witness, to almost all that happens in peoples lives, there are witnesses, always a ‘together’.

We pass a huge crater in the Al Wahd Street, just opposite the Al Qds community clinic. Its where a missile from either a Surveillance drone or F16 blasted Maysara Mohammad Adwan, a 47-year-old mother of 10, and 24-year old Ibrahim Shafiq Chebat into a pile of cement and clay-like mud. Ibrahim’s father, Shafiq Chebat, a classical Arabic teacher, was the first to uncover his body, but he did not immediately recognize his son. A Bulldozer was clearing debris when an arm was discovered. ‘I never expected to find him here’, he explained, ‘He was a civilian, he had gone to work at the 7-up factory, I thought he was at work’.

Because of an Israeli strike close to the factory in Salahadeen Street, staff were sent home early for their own protection. Shafiq’s sister in law Fatima explained to me, ‘The mud and the rocks, they were piled meters above his body, meters! It was two hours before they got to him. And then his father didn’t know it was him. It was his youngest son that said, ‘Its Ibrahim, Its Ibrahim’. And he said no my son it’s not him, but then we he wiped the mud from his face and when he saw it was him, he fell on the ground, he fainted on the ground’

Ibrahim had been working at the 7-UP plant to save money for his wedding. He was due to marry Selwan Mohammad Ali Shebat, a woman widowed before she could wed, she now describes herself as ‘broken’ and ’suffocated’ with grief. The women’s grieving room was full of mothers with lost sons, sitting around Ibrahim’s mother on gaudy sponge mattresses. Fatima and Kamela, sisters of Sadeeya, Ibrahim’s mother, had both lost a son each. ‘I am a mother of a martyr and she is a mother of a martyr, we are full of martyrs here’. Fatima’s son, Mohammad Kaferna, was killed by a tank shell in September 2001, whilst Kamela’s son Hassan Khadr Naim was killed by a missile strike in 2007.

Sadeeya was stunned and disorientated in her grief, throwing her arms up she keened over the memory of her dead son, ‘I said don’t go out, don’t go out, don’t go out, don’t go out’.

Sadeeya’s sister Kamela takes me by the eyes and leans forward. ‘They are using weapons of war against us’, she says. ‘ we’re civilians and they are bombing these neighbourhoods with war planes’.

Blue tarpolin grieving tents silence the streets of Beit Hanoon, like the rest of Gaza. Men sit side by side in lines on plastic chairs, taking bitter coffee and dates. With their quiet collective remembrance, they are the passage ways for too many families and communities into new levels of desolation and collective resilience.

So, I think we need to go back to 9am this morning. And the ‘it’ of what happened.

We had been talking to Sabrine Naim, in her rubble home when we heard two soaring, succinct, thuds. A plume of black smoke stormed up into the sky. We had though it was too far, maybe the outskirts of Beit Hanoon – in the end we go to Beit Hanoon hospital – the only one in town. Its a basic facility with just 47 beds, compared to Shifa’s 600, and no intensive care unit. With Beit Hanoon expected to be first in the firing line if Israeli ground forces invade, the Hospital is desperately under-equipped to cope. Two days ago it had just one ambulance. Now 5 have been scrambled from other local state and private hospitals and wait in the parking lot primed for the worst.

‘They’re bringing them in, they’re bringing them in’, we hear people say. I expect to see a wailing ambulance come veering round the corner, instead a cantering donkey pulling a rickety wooden cart vaults up to the hospital gate. Its cargo three blackened children carried by male relatives. They hoist their limp and contorted bodies into their arms and run in to the hospital. Their mother arrives soon after by car, running out in her bare feet to the doors.

Haya Talal Hamdan aged 12 was brought into the main emergency ward and lain down. She was soon covered with a white sheet, as her mother, comforted by relatives disintegrated into pieces. Ismaeel aged 9 came in breathing, his chest pushing up and down quickly as doctors hurriedly examined his shrapnel flecked body.

In the emergency operating theatre was Lamma, aged just 4. Opening the door, I saw a doctor giving her CPR, again and again, trying to bring her to life, but it was too late. She died in front of us.

Lamma’s mother blamed herself, ‘I asked them to take out the rubbish, to take out the rubbish, I should never have asked them to take out the rubbish’. A female relative was livid with disbelief, ‘She hadn’t even started school! We were, sleeping, and they call us the terrorists? How could they cut down this child with an F16?’

Doctor Hussein, a surgeon at Beit Hanoon Hospital said the cause of death was ‘multiple internal injuries and internal bleeding’. Their fatal injuries were consistent with their bodies having been ‘thrown up and down in the air 10 meters’.

Outside the hospital I turn around and see a young girl, maybe 10 years old, in a long skirt and slightly too big for her jacket. She’s beautiful, with straggly brown air and deep brown eyes. She’s on her own which is rare for any child here, they always stick together and move together. She looks eeriely alone, in the car-less empty street. I say hi and smile and she comes over and we shake hands, and I’m struck after the violence of the death of Lemma and Haya, and turmoil and out of control grief of the hospital at how vulnerable she is and how uncertain anything is about her future.

After the hospital, we made our way to the scene of the strike – Al Sikkek Street, close to the Erez Crossing. Two large craters around 6 meters in diameter and 20 meters apart scared an empty wasteland between a row of houses. One had turned into a lake; the missile downed power lines had smashed into a water pipeline, now spewing fresh water into the crater. Iman, 12 years old, a tough, long haired tom-boy wearing a wooly hat and jeans, witnessed the whole attack. She took us up the roof of her house to point out where and how and what she saw.

At the second crater, next to two green wheelie bins, we see a twisted bicycle and wooden cart, mangled together with plastic bags of rubbish that the children never got to dump. There is still blood on the ground. Crowds of young men gather to stare into the craters, and point to the gushing water mixing with sewage. They also point out a blasted building near by – its corner missing – a casualty of a 2007 Israeli missile attack.

We walk back to the mainstreet, now lined with solemn male, mourners, in groups talking quietly or looking listlessly at us. Iman explains to us, ‘I always ask God for me to become a martyr like the other children. My mother is always asking why, but they’re killing children here all the time, and if I die, then I prefer to be a martyr, like the others.

Even it’s better to die than live a life like this here’.

It happened at 9am this morning. We were speaking to Sabrine Naim at the time, standing and talking in the Naim family home which had been wrecked this morning. Chunks of debris – one a meter long and a foot wide – glass, and sharp slices of their own broken roof, had smashed onto beds, chairs, their kitchen and living room. Only two of their family of 12 had been home at the time. They were expecting an attack.

And it came at 4am – a missile strike by an F16 on the local police station and Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine offices.

Smouldering rubble and rocks and dust were strewn across the heart of Beit Hanoon – the market, taxi rank and main streat littered with debris.Sabrine had been hit in the face with small chunks of her neighbour’s home. One side of her right cheek was covered with a thick white dressing. She looked watery eyed and exhausted. Debris had also struck her in her heavily pregnant stomach. With only a month to go until giving birth, she spent two hours in the local hospital before being discharged.

The 4am blast shook us all out of our beds. A gigantic abrupt bang – the sound of concrete walls, floors and steel rods exploding on impact in an instant. The strikes had been happening all night – most of them in Jabaliya again. Distant thuds that you strain to map in your mind.

We had spent the night in Beit Hanoon, a town home to some 40,000 people in the North of the Gaza Strip. Beit Hanoon borders Erez Crossing and Houg (now called Sderot) in Israeli territory. The town possesses some of the most fertile land in Gaza. Much of it – orange groves and olive trees – has been bulldozed by the Israeli military to clear cover for fighter fire against Israeli settlements and towns. Even so, because of its’ proximity to Israeli towns, rockets have been known to be launched from here.

The family home we stayed in had been occupied by Israeli soldiers in the last invasion in 2006. The family of six was moved into the downstairs flat, whilst soldiers blasted holes in the walls of rooms on the top floor to make sniper posts. If the noise of an invasion – tanks, apaches, F16s, heavy boots, agitated soldiers and the never-ending sneer of the surveillance drones – didn’t keep the family awake. Then the sound of single shots and the wondering what or who had been hit, worrying that a neighbour or family member had been struck, would add to the internal invasion.

The house, located in a courtyard with olive trees and a roof with clear views of the surrounding streets made an excellent vantage point for snipers. Another home, of local doctor Mohammad Naim, a specialist in treating prematurely babies at Shifa Hospital had been occupied 12 times in the past 8 years by Israeli soldiers. He hadn’t even bothered to paint over the naked grey concrete smears in the walls in his upstairs room. They had been sniper holes. And he knew they would be back again.

His outside wall too, bore the spray painted orientation indicators typical of occupying soldiers moving through narrow alleys at night.

‘Do you think you’ll move if they invade?’ I asked him. ‘Where will I go?’ He said, ‘I haven’t got anywhere else to go?’. He showed me the lock of his front door, ‘This as been smashed open at least 20 times’ he remarked. Dr Mohammad had been blindfolded and taken to the agricultural school in Northern Beit Hanoon during the last invasion, along with all local men aged between 16-40.

He had been interrogated and detained from Thursday afternoon under Friday evening. ‘Every invasion they occupy my house. They cut the electricity and use their own flashlights. Last time my family were all downstairs for five days. My children are the worst affected, they remember everything, the tanks, the invasion, and being jailed; none of us are allowed to go out even when there is a break in curfew’. Asked how the soldiers behaved towards the family, he said, ‘Well it depends on the shift, sometimes they’re decent, sometimes they can be aggressive. But with the situation as it is now, any movement could attract fire’.

‘50 people were killed here’. This is my friend Sabr talking. He’s pointing to the street outside his sister’s home – another one always occupied by soldiers, like that of Dr Mohammad. In the last invasion, resistance had confronted advancing tanks. The result was a bloodbath. His family home had been leveled to the ground.

Walking through the streets here, nearly every house has a martyr – martyrdom status is attributed to anyone, young or old, fighter or civilian – who has been killed by occupation forces. It is a mark of respect, and a coping mechanism for the sheer volume of death and an inconsolable, mounting level of loss that affects every family. It is also a way to honour and pay tribute to lives violently taken, and let life live after death under occupation. Everyone knows a neighbour, a friend, a cousin, somebody who was killed by Israeli occupation forces. Communities here feel each death personally, because so many so know one another personally. The extended family lines and kinship networks that have grown up from the collective experience of dispossession and expulsion are a web of support and a common thread made solid in the form of houses built from tents, all close together and all bearingwitnesses together. Because the size of families and the proximity in which people live together, there is a natural participatory experience in almost every aspect of daily life. And every killing there is a witness, to almost all that happens in peoples lives, there are witnesses, always a ‘together’.

We pass a huge crater in the Al Wahd Street, just opposite the Al Qds community clinic. Its where a missile from either a Surveillance drone or F16 blasted Maysara Mohammad Adwan, a 47-year-old mother of 10, and 24-year old Ibrahim Shafiq Chebat into a pile of cement and clay-like mud. Ibrahim’s father, Shafiq Chebat, a classical Arabic teacher, was the first to uncover his body, but he did not immediately recognize his son. A Bulldozer was clearing debris when an arm was discovered. ‘I never expected to find him here’, he explained, ‘He was a civilian, he had gone to work at the 7-up factory, I thought he was at work’.

Because of an Israeli strike close to the factory in Salahadeen Street, staff were sent home early for their own protection. Shafiq’s sister in law Fatima explained to me, ‘The mud and the rocks, they were piled meters above his body, meters! It was two hours before they got to him. And then his father didn’t know it was him. It was his youngest son that said, ‘Its Ibrahim, Its Ibrahim’. And he said no my son it’s not him, but then we he wiped the mud from his face and when he saw it was him, he fell on the ground, he fainted on the ground’

Ibrahim had been working at the 7-UP plant to save money for his wedding. He was due to marry Selwan Mohammad Ali Shebat, a woman widowed before she could wed, she now describes herself as ‘broken’ and ’suffocated’ with grief. The women’s grieving room was full of mothers with lost sons, sitting around Ibrahim’s mother on gaudy sponge mattresses. Fatima and Kamela, sisters of Sadeeya, Ibrahim’s mother, had both lost a son each. ‘I am a mother of a martyr and she is a mother of a martyr, we are full of martyrs here’. Fatima’s son, Mohammad Kaferna, was killed by a tank shell in September 2001, whilst Kamela’s son Hassan Khadr Naim was killed by a missile strike in 2007.

Sadeeya was stunned and disorientated in her grief, throwing her arms up she keened over the memory of her dead son, ‘I said don’t go out, don’t go out, don’t go out, don’t go out’.

Sadeeya’s sister Kamela takes me by the eyes and leans forward. ‘They are using weapons of war against us’, she says. ‘ we’re civilians and they are bombing these neighbourhoods with war planes’.

Blue tarpolin grieving tents silence the streets of Beit Hanoon, like the rest of Gaza. Men sit side by side in lines on plastic chairs, taking bitter coffee and dates. With their quiet collective remembrance, they are the passage ways for too many families and communities into new levels of desolation and collective resilience.

So, I think we need to go back to 9am this morning. And the ‘it’ of what happened.

We had been talking to Sabrine Naim, in her rubble home when we heard two soaring, succinct, thuds. A plume of black smoke stormed up into the sky. We had though it was too far, maybe the outskirts of Beit Hanoon – in the end we go to Beit Hanoon hospital – the only one in town. Its a basic facility with just 47 beds, compared to Shifa’s 600, and no intensive care unit. With Beit Hanoon expected to be first in the firing line if Israeli ground forces invade, the Hospital is desperately under-equipped to cope. Two days ago it had just one ambulance. Now 5 have been scrambled from other local state and private hospitals and wait in the parking lot primed for the worst.

‘They’re bringing them in, they’re bringing them in’, we hear people say. I expect to see a wailing ambulance come veering round the corner, instead a cantering donkey pulling a rickety wooden cart vaults up to the hospital gate. Its cargo three blackened children carried by male relatives. They hoist their limp and contorted bodies into their arms and run in to the hospital. Their mother arrives soon after by car, running out in her bare feet to the doors.

Haya Talal Hamdan aged 12 was brought into the main emergency ward and lain down. She was soon covered with a white sheet, as her mother, comforted by relatives disintegrated into pieces. Ismaeel aged 9 came in breathing, his chest pushing up and down quickly as doctors hurriedly examined his shrapnel flecked body.

In the emergency operating theatre was Lamma, aged just 4. Opening the door, I saw a doctor giving her CPR, again and again, trying to bring her to life, but it was too late. She died in front of us.

Lamma’s mother blamed herself, ‘I asked them to take out the rubbish, to take out the rubbish, I should never have asked them to take out the rubbish’. A female relative was livid with disbelief, ‘She hadn’t even started school! We were, sleeping, and they call us the terrorists? How could they cut down this child with an F16?’

Doctor Hussein, a surgeon at Beit Hanoon Hospital said the cause of death was ‘multiple internal injuries and internal bleeding’. Their fatal injuries were consistent with their bodies having been ‘thrown up and down in the air 10 meters’.

Outside the hospital I turn around and see a young girl, maybe 10 years old, in a long skirt and slightly too big for her jacket. She’s beautiful, with straggly brown air and deep brown eyes. She’s on her own which is rare for any child here, they always stick together and move together. She looks eeriely alone, in the car-less empty street. I say hi and smile and she comes over and we shake hands, and I’m struck after the violence of the death of Lemma and Haya, and turmoil and out of control grief of the hospital at how vulnerable she is and how uncertain anything is about her future.

After the hospital, we made our way to the scene of the strike – Al Sikkek Street, close to the Erez Crossing. Two large craters around 6 meters in diameter and 20 meters apart scared an empty wasteland between a row of houses. One had turned into a lake; the missile downed power lines had smashed into a water pipeline, now spewing fresh water into the crater. Iman, 12 years old, a tough, long haired tom-boy wearing a wooly hat and jeans, witnessed the whole attack. She took us up the roof of her house to point out where and how and what she saw.

At the second crater, next to two green wheelie bins, we see a twisted bicycle and wooden cart, mangled together with plastic bags of rubbish that the children never got to dump. There is still blood on the ground. Crowds of young men gather to stare into the craters, and point to the gushing water mixing with sewage. They also point out a blasted building near by – its corner missing – a casualty of a 2007 Israeli missile attack.

We walk back to the mainstreet, now lined with solemn male, mourners, in groups talking quietly or looking listlessly at us. Iman explains to us, ‘I always ask God for me to become a martyr like the other children. My mother is always asking why, but they’re killing children here all the time, and if I die, then I prefer to be a martyr, like the others.

Even it’s better to die than live a life like this here’.

Mike Alewitz, American muralist, arrived in August to paint three walls, one in the Azeh refugee camp near Bethlehem, another in the Anatha camp near Jerusalem, and a third in the Arab village of Kufr Qara, located in Israel. (The Kufr Qara mural.) On August 4 he talked to an audience of activists and artists at the Baqa Center in Jaffa. He showed slides of his works – many of them landmarks in the struggle for labor rights. Several exist today in photos alone, for a mural is eminently destructible – and one that carries political punch, like Alewitz’s, will be sandblasted at a change of regime (like Mother Earth in Nicaragua) or upon rattling union fat-cats (like the P-9 mural in support of the meatpackers’ strike at the Hormel plant in Austin). These works and others were resurrected at the Baqa Center. When Alewitz mentioned his intention to paint at Kufr Qara, a young artist in the audience asked if he might help. Alewitz pondered a moment and said, “It’s not necessary for you to help me. If you want to be of help, then go paint a mural. There are plenty of walls out there. It’s not difficult. Any artist can do it.” He went on to say, “The conditions for change are in place. The time is right. We can prevail. But right here, right now, it’s up to you. The movement that is developing depends on you in this room.”

Who is Mike Alewitz?

Alewitz began as an activist. Art came later, as part of his effort to build a workers’ movement in America and abroad. He shook up many in the audience at the Baqa Center when, quietly and firmly, he named the US as the foremost terrorist nation on earth. He disturbed some among the artists too when he stated, without apology, that the goal of his art is to further social and political ideas. At one point he thanked the workers throughout the world who had forced him to discover visual images to express their struggle. He calls his genre Agitprop, short for “Agitation and Propaganda”.

Three local organizations hosted the Alewitz visit. Two work in the Occupied Territories: the Beit Jibrin Cultural Center in the Azeh camp and the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions. In Israel, the Workers Advice Center (WAC) hosted him for the week of August 3-8. WAC invited him to paint a mural in support of its campaign called “A Job to Win”, which seeks to put people back on the job in the construction industry – especially the Arabs, who were once the dominant labor force there.

Alewitz began making murals in the mid-eighties, after working as a sign and billboard painter. Since then he has painted in Nicaragua, Mexico, Chernobyl, Baghdad, and throughout the US – always in concert with the local unions. “The connection between mural painting and the labor movement is strongest,” he told Challenge, “at the moment of struggle, when the workers have a definite message to express. Then a painting becomes a significant weapon. For example, at the start of the Russian revolution, or the one in Nicaragua, public art played a central role.”

A mural, says Alewitz, can educate workers to solidarity while recalling forgotten parts of the local labor struggle. In the history of the working class, many stories – and inspiring figures – are virtually lost, because the capitalist class has taken care to expunge them. This working-class history, rescued from oblivion, can be a precious asset in the effort to organize. At the Azeh camp near Bethlehem, for example, Alewitz placed a huge loaf of bread in the center of the picture, together with a dozen red roses. He frequently uses this image, recalling the strike of the textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1912, when the women raised banners saying: “We want bread and roses!” If they focus only on job conditions (“bread”), unions fail to develop the workers’ consciousness (“roses”). Here, together with the unions, art can play a decisive role.

To the historical dimension Alewitz brings the spirit of the new era. “Access to art has been denied to workers. They were taught that it wasn’t for them, that they shouldn’t visit museums. There are workers who love to paint, but most will be embarrassed to tell you.” He adds, “When I come to a place, I can’t know the situation as well as the local people. Therefore, I look for subjects and images that are universal, that will be understood by workers everywhere. I paint people purple or green or blue, and sometimes I paint them without a clear gender – hermaphrodites. Agitprop artists need to experiment and develop an imagery to express the multi-hued nature of the workers’ movement today – and not to fall back on clichés.”

Alewitz remains a strong believer in activism. At the Baqa Center he said, “I have not come because I think I can change something here. I have come so I can take the images back with me and use them in the American working class, to show people how the situation here relates to their own.”

For more on Alewitz’s work, see Paul Buhle and Mike Alewitz, Insurgent Images: The Agitprop Murals of Mike Alewitz, New York, Monthly Review Press, 2002.

WAC’s Part in the Project

Alewitz and Christine Gauvreau direct the Labor Art and Mural Project (LAMP). In the spring they contacted us at WAC, saying they wanted to paint in Israel and Palestine. We were happy to offer our help – and a wall. The question was which wall? We have many work teams in many villages, but there would only be one mural.

Our choice fell on the village of Kufr Qara, for we had recognized one of its teams for excellence in 2002-03. The mural project set off a welter of activity in the village. People organized supplies, food and logistics. Toward the end of the first preparatory meeting, after the allotment of tasks, Farid Atamneh, himself an artist, said, “This is all very fine, but who’s going to paint it?” On hearing the answer, he exclaimed, “What! Him? To our village? All the way from America?”

Soon after his arrival, I accompanied Alewitz to a building site near Tel Aviv, where workers from Kufr Qara were on the job. In a conversation during the break, Alewitz stressed that George W. Bush does not represent the American people and certainly not its working class. He described the movement opposing the war and the part that labor unions have in the protest.

A week later, after he had finished the mural near Bethlehem, we met at the wall in Kufr Qara. Although on the edge of the village, it occupies 21 square meters at the entrance to a sports stadium serving the whole region. The local council had approved. The workers had cleared the area and erected a scaffold.

They returned from their day of labor and sat with Alewitz. He asked what they wanted the mural to convey. Among the responses was this: “We want a painting that will attract more workers to join us in WAC and help organize.”

In his preliminary sketches, Alewitz sought a picture that would answer to the workers’ need for a union to defend their rights while, at the same time, breaking the walls between workers that “Mr. Moneybags” erects to exploit them.

As the deadline approached, Alewitz accepted the help of local artists, including two from WAC. The work each day went from sunrise to sunset, 14 hours. The only breaks were for food in the homes of the workers, who took turns hosting the team. On the last day, with the dedication ceremony scheduled for the evening, there wasn’t even time to leave for a meal. Muss’ab Atamneh, whose turn had come to provide the food, would not be daunted. The astonished painters watched as serving dishes appeared: dozens of courses spread on carpets among the cans of paint and the brushes.

Workers and Artists Speak

Muss’ab Atamneh was among the most active in organizing the Alewitz visit to Kufr Qara, and he also took part in the painting. He says: “The visit helped deepen the connection between WAC and the village. People were astonished that WAC would bring an American artist to us. Apart from this, the artistic result was a delightful surprise. My team workers tell me they are getting enthusiastic responses from the neighbors. Although the soccer season hasn’t yet begun, people drive out to the stadium to look at the mural. Personally, I think it’s very important to us, the members of WAC, because it shows that WAC is concerned not only with our working conditions, but also with the lives we live when the work day is done.”

Ra’afat Khattab is an art student in Jaffa and a leader of its Baqa Center. He took part in the project from start to finish: “This experience has been most important to me. In my work at the Baqa Center, I take it as a guiding principle that art should contribute to social progress, but that goes against what I’m learning in college. There, and in the Israeli artistic milieu generally, they sanctify individualistic art. In working with Alewitz, I saw what potential there is in the genre of mural painting.”

Hillel Roman, a young artist from Tel Aviv, works as a volunteer with children at the Baqa Center. He also took part in the painting. “At the lecture in Jaffa, it was impressive to hear an artist who travels throughout the world engaging with workers and taking part in their struggles. I was also struck by his work, which goes against the stream of establishment art in galleries and museums. I was interested to hear his opposition to the existing order, how he identifies with the oppressed. I asked myself at once, of course, how come I sit at home or show my work in a gallery. He explained very well that in galleries and museums, the level of our opposition as artists is limited to the existing order, because otherwise they simply won’t show our work. So I asked myself, What then? Am I a collaborator?

“On the other hand, I think the question is more complex. I still prefer to make a division, to keep what I create as a tool for personal expression, and to contribute to society in other ways, as when I volunteer at the Baqa Center, teaching kids to express themselves through painting… About the notion of ‘art for a cause’, I think art is the stepchild of two classes: it is crushed between the bourgeoisie, who speculate in it and stick it in museums, and the working class, who flatten it into ideology (even if the latter has merit). Art never reaches the point of identifying with either class, or when it does so, it ceases to be interesting. Alewitz concedes that he is making propaganda, and as such his work has a lot of power.”

The Kufr Qara mural was unveiled on August 8 toward evening. Its bold orange sky glows above the solid green of its hills and the blue silhouettes of cities. We see two panels, almost symmetrical, each with a wall, partly broken, stretching from the foreground into the distance. Asymmetry is provided by Mr. Moneybags, who escapes with the loot on a flying carpet. Out of the earth arise great fists, brick-red, clenched in labor’s traditional gesture of defiance and solidarity. Banners proclaim the message in Arabic, Hebrew and English: “No Walls Between Workers!”

Sindicalismo Sin Fronteras

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Art/Design, Culture, Industrial Unions on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Sindicalismo Sin Fronteras

by Mike Alewitz

Assistance by Daniel Manrique and numerous volunteers

Approx. 8′ x 30′

Frente Autentico Trabajadores Auditorium

Mexico City 1997

On April 5, 1997, a public inauguration of two new murals was held at the auditorium of the Frente Autentico Trabajadoras (FAT) in Mexico City. The event was part of a cross-border organizing project of the FAT and the United Electrical (UE) union. The following is based on a dedication speech given by artist Mike Alewitz of the Labor Art and Mural Project (LAMP).

Sisters and Brothers:

It is a humbling experience to come to Mexico to paint, for this country is the home of the modern mural movement, and gave birth to some of the greatest public art of this century. Here is where the Rivera, Orozco and Siqueras were inspired by millions of peasants and workers to illustrate the historic conquests of the Revolution. On a smaller scale, we are attempting to illustrate the UE-FAT efforts to build international solidarity and cross-border organizing.

It was Emiliano Zapata who gave the greatest political expression to the Mexican revolution, and it is under his watchful eyes that our mural unfolds. We have also included the figures of Albert and Lucy Parsons. Albert was one of the Haymarket martyrs, framed up and executed for his leadership in the Chicago labor movement’s fight for the eight hour day. Lucy was also a leader in that movement, and she continued her labor and anarchist activities until she died at an old age. She was of African-American and Mexican ancestry, was an early leader of the feminist movement, and a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World. The Parsons hold in their hands some bread and a rose. “Bread and Roses” was a slogan of the Lawrence textile strikers; women who demanded not only the bread of the union contract, but the rose to symbolize that workers deserve a rich spiritual and cultural life.

The quotation in the painting is from August Spies, also executed on November 11, 1887. “If you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labor movement…the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil in want and misery expect salvation-if that is your opinion, then hang us! Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you-and in front of you, and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.”

How fitting a quote for this land of volcanos. This is precisely what is happening today, as first a Los Angeles, and then a Chiapas explode, here and there, precursors of a generalized conflagration. Our class is like the core of the earth, being compressed under ever greater pressure, until forced to explode.

We are using this cultural project to illustrate our collective union vision. Unions are the first line of defense for workers. They keep us from getting killed or poisoned. They allow us some basic human dignity.

Unfortunately, too often our unions resemble exclusive clubs, or worse, criminal gangs. Even unions that pride themselves on being progressive are often beaurocratic and autocratic. Without the full and active participation of the membership, all the weaknesses of our organizations emerge. As workers, we often must not only battle the employers, but our own conservative leaderships as well.

This is a particular problem in the United States, where employers keep us stratified and divided. They attempt to pit low-wage workers against the more privileged. They use divide-and-conquer tactics to convince us to be for “labor peace.” But labor peace is the peace of slavery, wether in the U.S. or in Mexico.

The Frente Autentico Trabajadoras is helping to lead the struggle for genuine union democracy. There have been, and will continue to be casualties in this historic fight. And today we dedicate this mural to those who have been victimized in the struggle for union democracy. This mural is the product of not only artists, but the thousands of workers who built our unions. This is their mural.

Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to denounce the criminal policies of the United States government. In particular I denounce the economic sabotage of Mexico and the criminal embargo of Cuba. The gang in Washington does not speak for me or millions of other American workers. They are waging war upon our class. They are my enemy and your enemy. They represent the past, we are the future. If we continue to forge these links of solidarity, they can never prevail.

Art and Social Movements

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Art/Design on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Justseeds/Visual Resistance Artists’ Cooperative is a decentralized community of artists who have banded together to both sell their work online in a central location and to collaborate with and support each other and social movements. Our website is not just a place to shop, but also a destination to find out about current events in radical art and culture. Our blog covers political printmaking, socially engaged street art, and culture related to social movements. We believe in the power of personal expression in concert with collective action to transform society.

Education Not For Sale

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Education on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Education Not for Sale is a network of anti-capitalist students founded in September 2005. We exist to fight the rule of profit in our education system and in society as a whole, seeking to organize students alongside workers in struggle to replace capitalism with a society based on collective ownership, social provision for need, ecological sustainability and consistent democracy. We organize in the National Union of Students, in student unions, on campuses and in a variety of campaigns and movements.

We fight for:

- Free, top-quality, secular and democratic education and public services at every level, funded by taxing the rich and business.

- The abolition of all fees and a living, non-means-tested grant for every student, in FE and HE.

- Education not profit: business out of our schools, colleges and universities. Institutions run democratically by students, education workers and communities and aimed at developing free human beings, not teaching factories run by bureaucrats to make a profit and produce compliant workers.

- Mass direct action to win our demands, a campaigning NUS which mobilises such action – and a rank-and-file movement of student unions and the activist left prepared to take up the fight in opposition to NUS’s current right-wing leadership.

- Mass involvement and democratic control in NUS and student unions: for fighting unions, not bureaucratic service-providers.

- Student-worker unity; a fight to organize students who work; consistent support for workers’ struggles, on campus and beyond, in Britain and worldwide.

- Consistent support for women’s, black, LGBT and disabled liberation. Defend the NUS Liberation Campaigns. Free abortion on demand; free 24 hour nurseries and other social provision to liberate women from domestic drudgery. Militant opposition to the BNP, no platform for fascists. Fight racist lies, defend asylum-seekers, no borders.

- A political, internationalist student movement turned outwards towards the anti-war, climate change, global justice and anti-capitalist movements.

- Opposition to imperialism. The immediate and unconditional withdrawal of all troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. We oppose any war and sanctions on Iran. In the event of an attack on Iran, we will launch a direct action campaign at campuses across the UK, along with student Stop the War groups.

- Solidarity with student, workers’, women’s and other movements fighting exploitation and oppression everywhere. Solidarity with the Palestinians in their struggle for self-determination.

- Left unity. The organizations of the student left should unite – maximum unity in action, free and open debate about our differences and disagreements.

Agreed at the Reclaim the Campus campus, May 2008

We call on all student activists and organizations who broadly accept this statement of aims to support ENS.

Advisory Service for Squatters

Posted in Uncategorized, tagged Housing on January 4, 2009| Leave a Comment »

Advisory Service For Squatters is an UNPAID collective of workers who have been running a daily advice service for squatters and homeless people since 1975. It grew out of the former Family Squatters Advisory Service, which was founded in the late 1960s. ASS publishes The squatters Handbook, the twelfth edition of which is the current one, and has sold in excess of 150,000 copies since 1976.

As we are short of volunteers and money we are rarely able to help students, journalists etc., who so often seem to want us to do their article/project for them. This website has been set up to try to provide all the necessary information without taking up our volunteers’ scarce time. In the resources section you can find articles, documents and various information about squatting including history and ‘squat zines’. There is also a gallery with photographs strecthing back over 30 years.

You Can Contact Us

By telephone on :

020 3216 0099 or 0845 644 5814 ( if phoning in UK outside London from a landline )

Fax us: 020 3216 0098

Office Opening hours:

MONDAY to FRIDAY 2-6pm

(NOT Saturday/Sunday) . Don’t leave it to the last minute before contacting us as we are always busy:-) N.B. If you wish to call in at the office, please phone first.

You can order The NEW Squatters Handbook (12th edition ) from Advisory Service For Squatters, 84b Whitechapel High St, London E1 7QX.